Learning the language of proteins

Amino acids in a protein are analogous to letters in an alphabet, short subsequences of amino acids are analogous to words in an unknown language, and a protein’s entire amino-acid sequence to a document encoding its structure and function. Therefore, I applied techniques from natural language processing to learn the language of proteins. Given a large collection of unlabeled texts, word2vec and doc2vec are well-established methods that learn to convert words and documents to vectors that capture their meaning. Similarly, using a large collection of unlabeled protein sequences, I trained a model that learns to vectorize proteins such that similar vectors encode similar proteins. These vectors can then be used in machine-learning models that predict protein properties from small amounts of labeled data. Models built using these vectors predict protein properties without explicit knowledge of the protein’s structure or the properties of its amino acids. Instead, the encoding process transfers information from the unlabeled sequences to the prediction problem.

Learn to encode proteins

I spent the first part of my PhD using machine learning to predict protein properties from small sets of measured sequences. The first step of a machine-learning pipeline for proteins is encoding the proteins. We used what’s known as a one-hot encoding. For example, if I want to encode the DNA sequence AGTT, then I can encode each position using three 0s and one 1. Of course, for proteins, I would need 19 zeros and one 1 for each position.

One-hot encodings are a good default. They do, however, have some drawbacks. One-hot encodings are space-inefficient and don’t account for the amino acid properties. There are lists and tables of amino acid properties, but different problems will require different properties, and it’s not obvious beforehand what those are. One-hot encodings are also surprisingly difficult to implement correctly. This quarter, I TAd a class where we had the students reproduce many of my results. Helping them with their homework, I noticed that the single most difficult part was making the one-hot encodings of the sequences. This gets even worse when you don’t have a TA who picks out all the sequences for you and pre-aligns them! So if we’re training models to predict protein properties from data, why not train models to encode the proteins too?

Of course, I’m not the first person to have this idea. In natural language processing, there’s an analogous problem when encoding sequences of words. Starting with word2vec, people have used learned vectors to represent words and sentences. (These are often known as ‘embeddings’ because they ‘embed’ words into a vector space). Other people have explained these in much more detail (and much better than I can). For example: word2vec, doc2vec. These all use the assumption that similar words occur in similar contexts to learn embeddings that place words with similar meanings close together in the embedded space. They’re generally trained on massive datasets, such as all of Wikipedia. This means that, in addition to providing a convenient representation, they also encode information from massive (and free) unlabeled datasets, which improves performance on a variety of tasks.

For example, if I want to train a model to learn whether movie reviews are positive or negative, I need a dataset of reviews that are labeled as positive or negative. That usually means that somebody has to manually label the reviews, which puts an upper limit on how many examples I can obtain. On the other hand, downloading all of Wikipedia is quick and easy. Likewise, I work with small sets (< 300 sequences-label pairs) of labeled protein sequences, but I can also go and download 500,000+ protein sequences from UniProt.

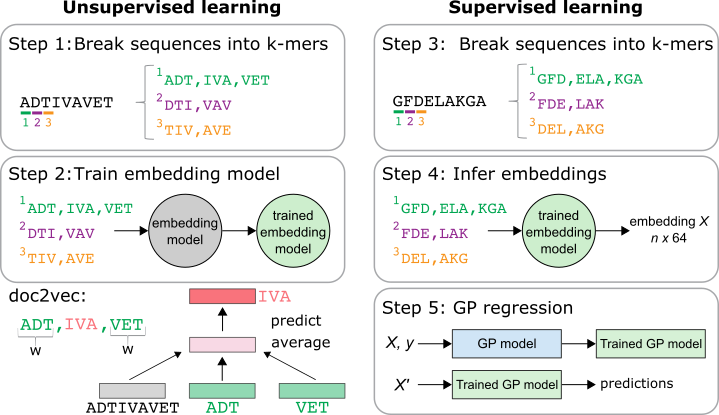

Inspired by doc2vec, I created a two-part pipeline for embedding sequences of interest. First, unsupervised doc2vec embedding models were trained on proteins downloaded from UniProt. Instead of ‘words,’ we have ‘k-mers’, which I obtain by chopping each protein up into subsequences of length k. For example, for k = 3, there are three lists and each list begins at one of the first three amino acid positions of the sequence. Doc2vec learns an embedding for each overall sequence and for each k-mer. I chose to use 64-dimensional embeddings.

Once I have this unsupervised embedding model, I can use it to encode sequences of interest by first chopping them into k-mers of the same size. These encodings then serve as inputs in Gaussian process (pdf) regression models.

Encodings enable accurate models

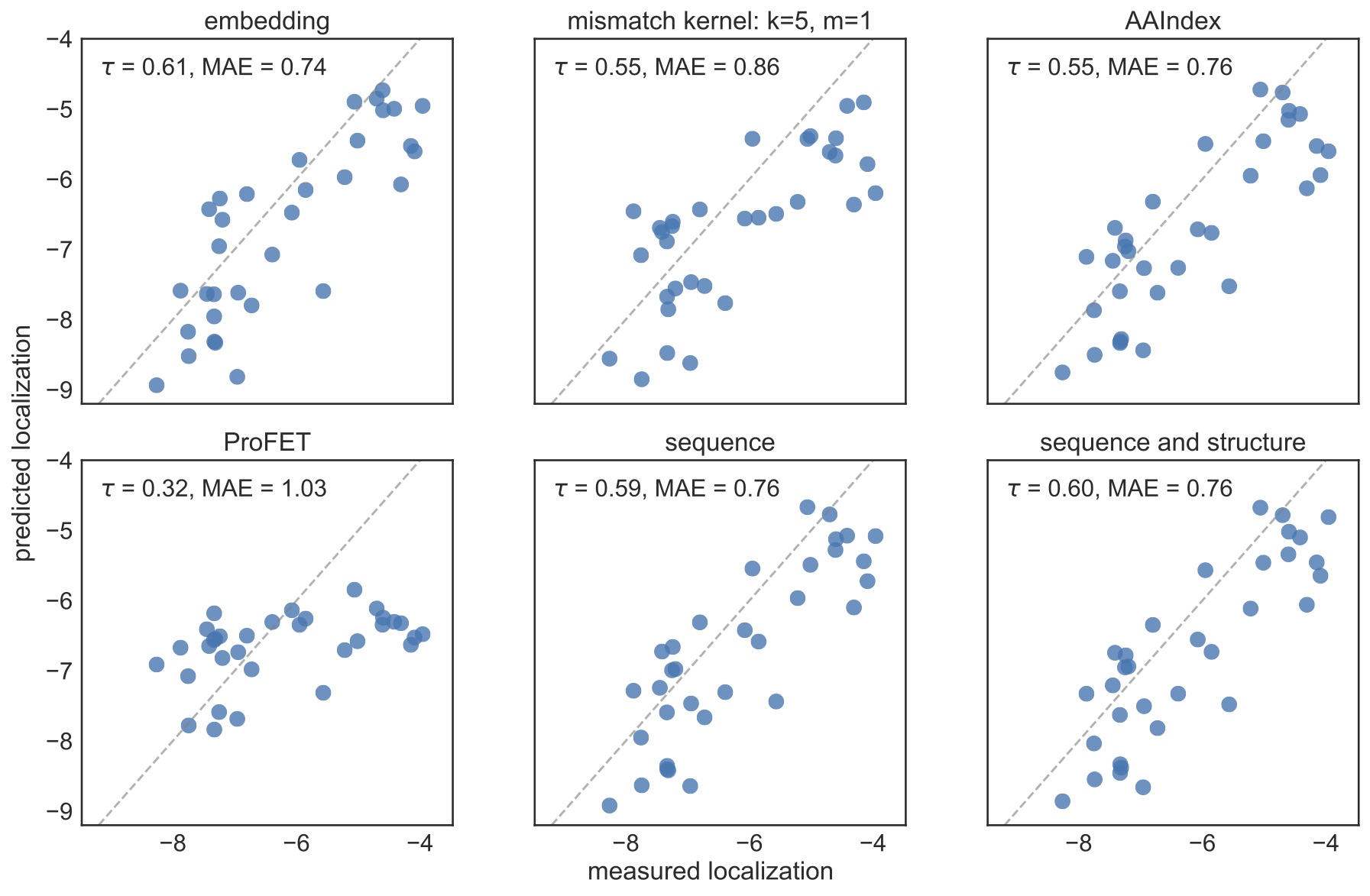

I tested embeddings on four protein prediction tasks, comparing their performance to one-hot encodings of sequence or sequence and structure, encodings based on physical properties (AAIndex and ProFET), and string mismatch kernels. For all of these tasks, the embeddings performed at least as well as the other methods despite not using alignments, structural information, or physical properties. For example, here are the test predictions for channelrhodopsin localization, where embeddings have both the highest Kendall Tau and lowest mean absolute deviation.

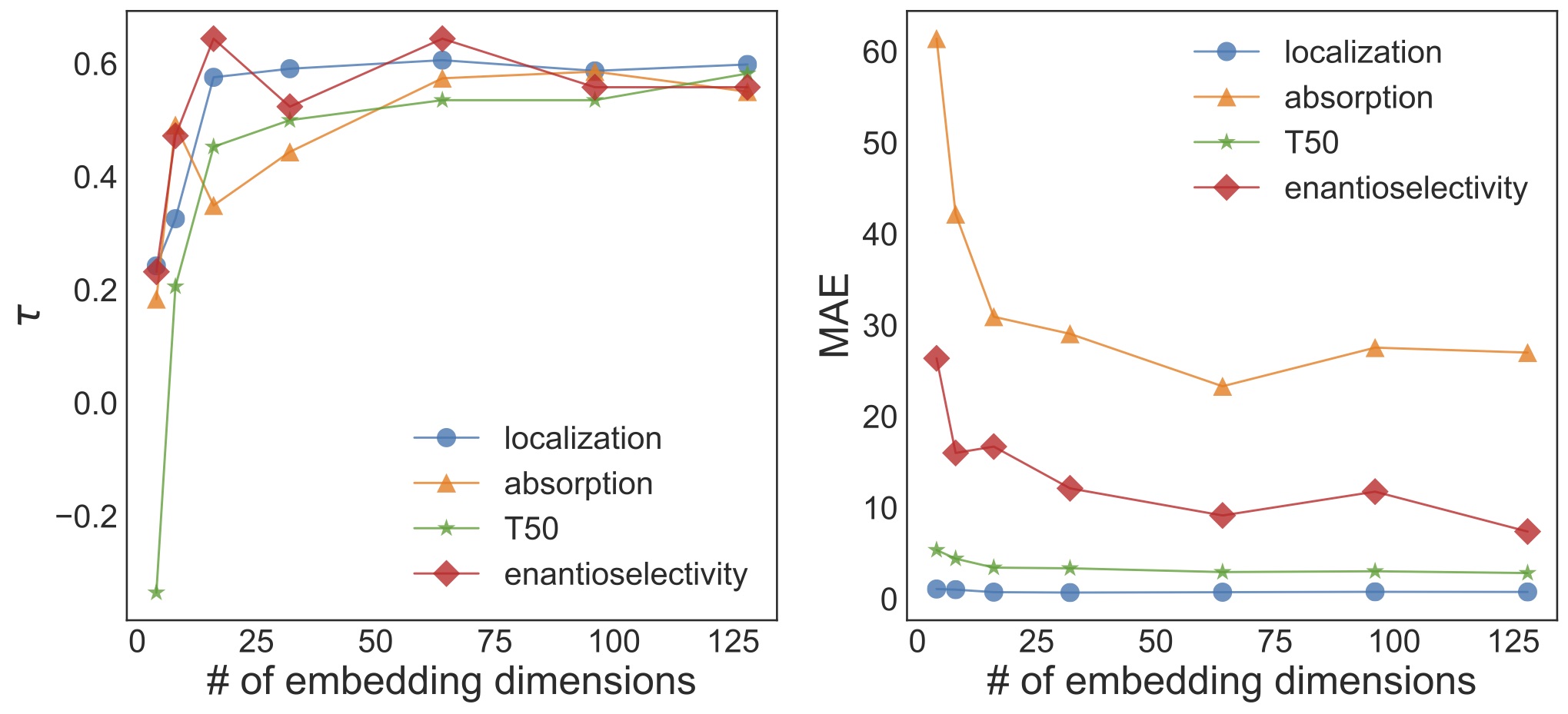

I chose to use 64-dimensional embeddings, but it turns out that I can still train reasonably accurate models after reducing the number of embedding dimensions to 16.

Think about this for a minute. The protein of interest has over 200 amino acids. Protein translation and trafficking is a multi-step, poorly-understood process. Previously, we had found that there are no simple sequence or structure predictors of membrane localization. But I can store enough information in 16 numbers to predict how well it will be trafficked to the cell plasma membrane.

Further reading

The full paper is available at Bioinformatics: Learned protein embeddings for machine learning, and code to reproduce the results is available here.